|

| Senator Bill Raggio, Nevada State Senate Majority Leader |

Thirteen

years ago, in November 2010, little-known, far-right Republican candidate

Sharron Angle was on the verge of defeating U.S. Senate Majority Leader Harry

Reid in what was shaping up to be one of the greatest upsets in American

political history. Though polls showed Democrat Reid to be widely unpopular

with Nevada voters, over two hundred high-profile Nevadans, under the

organizational title "Republicans for Reid," rallied to provide endorsements

that proved instrumental in Angle's subsequent defeat.

Longtime Republican State Senator Bill Raggio

did not join that list; instead, he made a forceful, independent declaration he

hoped would open the eyes of his party to the direction it was heading. He

explained that he could not endorse Angle because of her "inability or

unwillingness to work with others, even within her own party, and her extreme

positions on issues such as Medicare, Social Security, education, veterans'

affairs, and many others."

Raggio

qualified his decision by saying he did not agree with Senator Reid on much of

his agenda. Still, as U.S. Senate Majority Leader, arguably the second most

powerful person in the country, Reid would better represent the interests of

Nevada than a novice "backbencher" like Angle. As such, Raggio concluded: "I

will reluctantly vote for Senator Reid's reelection."

Ultraconservatives, who had been gaining ascendancy in the GOP, were furious. The State Senate

Republican Caucus quickly drove Raggio from his longtime leadership role. He

subsequently resigned his Senate seat. Disowned by many supporters and even lifelong friends, organizations

that had once bragged of Raggio's membership now distanced themselves.

Though disappointed, Raggio did not back down, publicly sounding the alarm that extremist factions within the state and national GOP would soon take control and that their refusal to negotiate, in a zealous crusade for ideological purity, would fracture, and consequently weaken, the party to a point where it would no longer be acceptable to a majority of American voters. After decades of right-wing pundits perpetuating the belief that government was an enemy of the American people, Raggio said, ultraconservatives were willing to shut it down unless others accepted their nonnegotiable social and fiscal agendas.

Raggio

had always considered himself a conservative champion of individual rights,

limited government, and fiscal responsibility, but in a way that would, as he

often said, deliver "lean government, but not a mean government." With this

philosophy as his guide, he led the State Senate for decades with a willingness

to listen and consider the opinions of others, gaining trust on both sides of the aisle. Partisanship was minimal, and legislators generally worked together for the

common good. Raggio understood the axiom attributed to President Ronald Reagan:

"The person who agrees with you 80 percent of the time is a friend and an

ally—not a 20 percent traitor."

*****

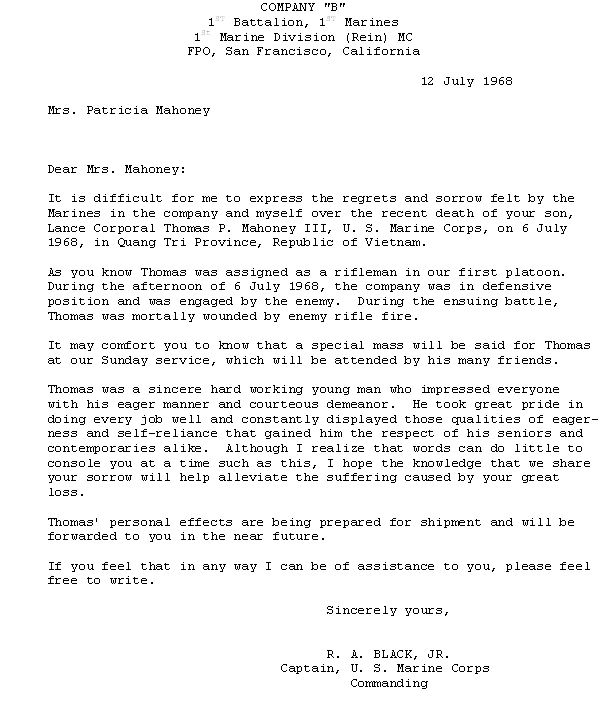

|

| Bill Raggio with President George H.W. Bush |

I came to know Senator Raggio in 2003 when I was assigned as a staff member to his Committee on Finance at the Nevada Legislature. My first book, A Patch of Ground: Khe Sanh Remembered, a memoir of my time as a young Marine during the 1968 siege of Khe Sanh in South Vietnam, was released the following year. Knowing Raggio had been a World War II-era Marine officer, I slipped him a copy in a hallway one Friday afternoon. He read the book that weekend and asked if I would write his biography.

I

spent the next several years researching his personal life and career. During

that time, we met frequently for interviews, supplemented by dozens of

discussions with his legal and political colleagues—friend and foe. In

addition, as a Finance Committee staff member, I observed Senator Raggio daily

during biennial legislative sessions over eight years. The result was A Man

of His Word: The Life & Times of Nevada's Senator William J. Raggio,

published in 2011.

I

learned that Raggio's reputation predated his time in the state

senate. Upon his election as Washoe

County District Attorney in 1958, Raggio had set about cleaning up widespread

corruption in the Reno city government and police department, generating

threats against him and concerns about his family's safety.

His

contentious relationship with Nevada's flamboyant brothel owner, Joe Conforte,

culminating in a bungled attempt by Conforte to blackmail Raggio, resulted in a

conviction for extortion. The lewd content of the trial made it a sensation for

its time, covered by national and international news services. As Raggio's fame

for being a colorful and effective prosecutor grew, he received several

prestigious awards and honors. In 1967, after being named District Attorney of

the Year by the National District Attorneys Association, Raggio was elected its

president—remarkable recognition for a prosecutor from a small western county. He was soon sought after by heads of state and other significant government and

national political figures.

In

those days, Northern Nevada hosted topline entertainment, and Raggio's outgoing

personality resulted in long friendships with some of the country's foremost

performers. Most notable among them was Frank Sinatra. When Nevada gaming

officials forced Sinatra to surrender his gaming license as a result of hosting

a Chicago mobster at his Cal Neva Lodge at Lake Tahoe, Raggio remained loyal

despite being the top cop in the county where that occurred, raising eyebrows

and providing fodder for his political foes.

When

Frank Sinatra Jr. was kidnapped at Lake Tahoe, but outside Raggio's

jurisdiction, Bill Raggio was one of the first people Sinatra called on for

assistance. In later years, when Sinatra sought a new gaming license in Nevada,

it was Raggio who, in private practice as one of the top gaming attorneys in

the state, successfully pled the case before the Gaming Control Board despite

evidence that Sinatra had continued to associate with members of organized

crime.

As his

fame grew, Raggio always kept in mind the people he was elected to serve. Las

Vegas Review-Journal reporter Jude Wanniski marveled at Raggio's wit and

ability "to remember the name of nearly every person he ever met:

.JPG) |

| Bill Raggio representing Frank Sinatra before the Gaming Control Board. |

"In

Reno, it's virtually impossible to sit and talk to him for ten minutes without

interruption. In restaurants, the cook comes out of the kitchen to say hello to

him. On the street, the truck drivers honk at him, cabbies slow down, yell and

wave to him. A hotel porter is sifting

cigarette butts out of a wall sandbox; Raggio, walking by, hails him: 'Freddie,

you find any gold yet?' and the porter turns around and grins."

Just before leaving on an Australian vacation

in late February 2012, Raggio called me to discuss an upcoming book signing we

had scheduled in a few weeks at the Wynn Las Vegas. He assured me that he was

happy to attend despite dealing with the pain of a torn Achilles tendon and

some difficulty breathing. I was not surprised by his thoughtfulness. It would

be the last time we spoke. He died three days later from respiratory failure in

Sydney at age 85.

Until

the end, despite all it cost him, he never regretted his outspoken resistance

to those he felt had "hijacked" his GOP or doubted for a moment that he had

acted in the best interest of all Nevadans.

I've recently completed a book manuscript, Nevada Senator Bill Raggio and the

Politics of Divisiveness, which describes these momentous changes in the climate

of Nevada and national politics over the last four decades. I hope to see it

published next year.

During

law school, Raggio excelled in real property law, owing to his innate

mathematical skills, and thought he might concentrate his practice in that

field. However, he soon learned that in the early 1950s, most attorneys in

Nevada did not have the luxury of specializing in a single facet of the

law.

"In

Reno," he later said, "you were always assured of getting nasty divorce cases

to cover your overhead — although I never wanted to be a divorce lawyer. I had

also decided that I was really not suited for criminal law."

He

would revisit that self-analysis after a call from Nevada's finest trial

attorney, Peter Echeverria. Echeverria would later serve as a National

President of the American Board of Trial Advocates and precede Raggio in the

Nevada State Senate, the first senator of Basque heritage, and later become

head of the Nevada Gaming Commission. His reputation was impeccable.

In the

early 1950s, Echeverria left the prestigious Woodburn firm in Reno, hoping to

make a reputation by winning a high-profile case, and found one made to order,

with elements of the Old West and a salaciousness the public had come to expect

from a good Nevada story. Echeverria asked Raggio to assist. Though he would

not be paid, the young attorney jumped at the opportunity to earn experience

with the legendary Echeverria.

On

trial for his life was mineworker Ray Milland, who had been charged with

murdering a prostitute at Taxine's brothel in Tonopah. The legalization of

brothels was then, as it is today in Nevada, left to the discretion of local

governments.

Although

there were no eyewitnesses to the crime, Milland had been accused of being the

killer by a local hoodlum, Bonny Ornelles. Even before the trial began, it was

apparent to most of the townspeople, as well as both defense attorneys, that

the more aggressive Ornelles had committed the murder. The meek Mr. Milland,

self-admittedly a brothel customer that day, was a victim of circumstance.

Echeverria

and Raggio spent several days interviewing witnesses in preparation for the

case. Whether out of loyalty to Ornelles or fear of reprisal, it was soon

evident that their stories were largely contrived.

Judge

William Hatton presided over the trial in the old Nye County Courthouse, a

rusticated stone structure with a slender silver dome at the southern edge of

Tonopah. A mining boomtown earlier in the century that once held a saloon operated by legendary lawman and later "political fixer" Wyatt Earp, Tonapah was now a small nearly forgotten community in the high desert of central Nevada. While Echeverria handled most of the courtroom work, he did allow his

young assistant to cross-examine a few witnesses. The process enthralled

Raggio, who would later describe the principals as "colorful local

characters, most of whom had few aspirations in life other than hanging around

a brothel."

One,

in particular, Billy Gallagher, tried to hide the fact that the brothel

employed him as an errand boy. Under repeated questioning, Gallagher insisted

he did not work for Taxine's but rather did odd jobs around town. When Raggio

asked what kind of "odd jobs" he performed, Gallagher replied, "I mow

lawns." With that, the courtroom audience and jurors burst into uproarious

laughter because, at that time, there was not a square inch of lawn in all of

dusty Tonopah.

Milland

would be acquitted, and, for years afterward, Raggio half-jokingly insisted

that his coaxing of the lawn-mowing lie from a dimwitted Mr. Gallagher was

instrumental in swaying the jury. Bonny

Ornelles, the likely killer, was never charged with the crime. Raggio believed

he died sometime later "of something other than natural causes."

Raggio

now had an exciting criminal trial "under his belt" and a proper and

popular verdict. Though stimulated by what he had experienced, he was still

looking for his professional niche because the Milland murder trial awakened in

him certain realities concerning a thorny facet of the legal profession:

"In criminal cases," he later said, "justice is not always served. A truly professional attorney will feel obligated to ensure proper procedures are followed — even if they believe or know their client committed the crime. The innocence or guilt of defendants in the few criminal cases I defended was so indisputable that I was never put in a position of moral ambivalence." In other words, he had never defended an individual he knew to be guilty.

Bill Raggio represented so few criminal defendants in his career, thus escaping that ethical dilemma, mainly because he would spend the next eighteen years trying cases from the opposing side as a prosecuting attorney. He would go on to become one of the most highly respected prosecutors in the nation—not a bad ending for someone who once felt he was "really not suited for criminal law."

.jpg)

%20-%20Copy.JPG)

.jpg)